USask researcher participates in national water survey as part of oil sands research

Scientists are studying ways for plants and their associated microbes to clean up wastewater from oil sands operations.

This would be accomplished through the development of wetland treatment systems. The big question is: will the public support such an approach?

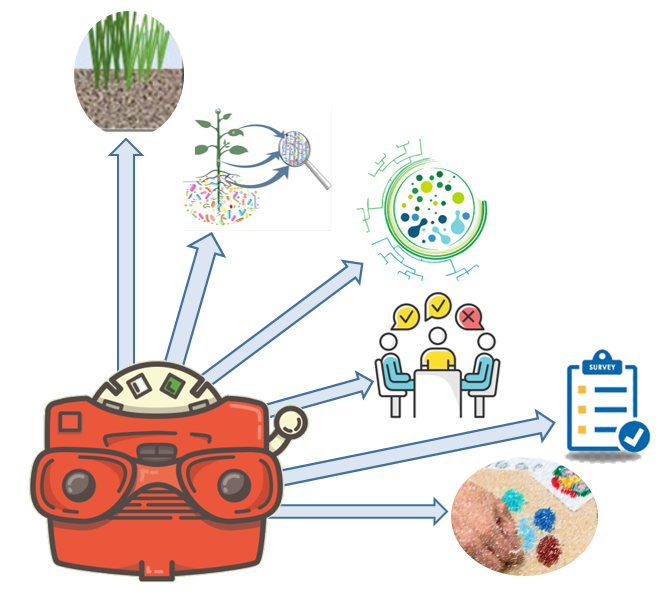

University of Saskatchewan (USask) scientists are part of a Canada-wide team aiming to find out by studying how researchers, industry partners, and communities can work together to enhance wetlands. The team, guided by Indigenous partners, will do laboratory and field science, conduct decision experiments and social network mapping, create a national public survey to gauge the extent to which people value technologies that harness the power of ecosystem services in the natural environment, and look at the problem through artistic lenses.

A section of the team, led by Dr. Lori Bradford (PhD) at USask, is studying the social sciences aspect of the research to explore legal, social and economic gaps in knowledge and practice.

“With a window opening for people to have their say in the technologies we use to restore landscapes, and the regulations used to monitor and measure that restoration, the time for this project is now,” said Bradford.

“We are working to use many different ‘languages’ in this work: the language of economics, Indigenous knowledge, law, and, art, are being put to use by our team,” she said. The team also includes Dr. Graham Strickert (PhD), assistant professor in the USask School of Environment and Sustainability (SENS), and Dr. Jason MacLean (PhD), assistant professor in the faculty of law at the University of New Brunswick and adjunct professor in SENS.

The project, Application of Genomics to Enhance Wetland Treatment Systems for Remediation of Processed Water in Northern Environments, is being led by Dr. Douglas Muench (PhD) at the University of Calgary and Dr. Christine Martineau (PhD) at Natural Resources Canada, and is supported by a grant from Genome Canada.

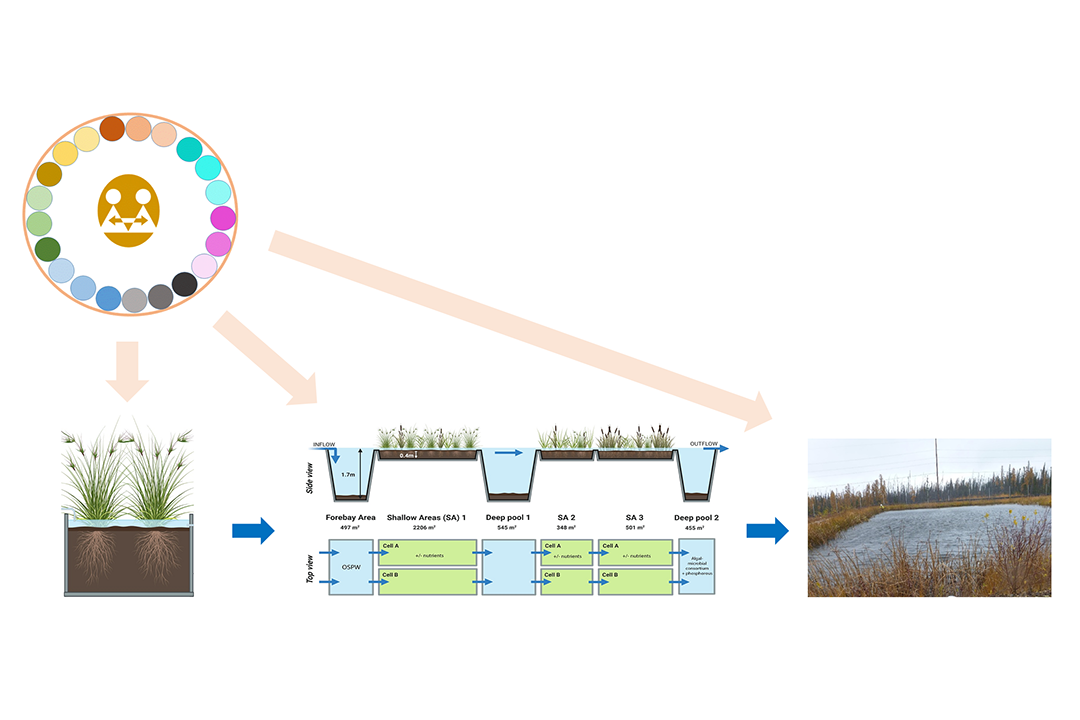

A natural way to clean up large volumes of wastewater is through a constructed wetland treatment system, which uses vegetation, soils and organisms to filter and process suspended solids and trace metals.

The national research team is studying how genomics in the system’s plants, soils and organisms can be harnessed to biodegrade toxic organic compounds such as naphthenic acids.

According to the team, the proposed applied research will provide insight on the mechanisms of plant-microbe interactions to facilitate the development of a robust, ‘green’ and cost-effective system for the remediation of oil sands process-affected water.

Brock University economist Dr. Diane Dupont (PhD) is leading a sub-section of the research that will examine the Canadian public’s perspectives on the use of these genomic methods in the context of oil sands remediation.

“I'm really looking forward to working on this project,” said Dupont. “I see it as a really great opportunity to inform the general public about the role ecosystem services play and how important it is to better understand the values provided by these services.”

The surface mining of oil sands is a large industry in the Athabasca region of northern Alberta. While no release is currently allowed, future legislation will require operators to restore the water before release, and to remediate the landscape.

Dupont said social benefits from a constructed wetland treatment system that safely and effectively treats oil sands process-affected water have several important benefits.

These include potential cost savings from use of natural processes to sustainably deal with industrial effluents, as well as the potential for a shorter time period needed to achieve good water quality.

“In turn, this may mean fewer health damages from toxic releases,” she said.

Bradford said she expects the social science program will help future social and natural scientists prioritize their work through being guided by stakeholder and public interest, and also inform policymakers about the preferences and knowledge level in the general public.

“I’m excited to see how Genome Canada as a funding organization is requiring that social sciences be embedded in their large-scaled programs. There is a need for our disciplines to work together on the complexity of problems where genomic sciences can be applied, and in this project, we have been given the opportunity to explore solutions to an environmental problem through many lenses.”

The team will be working with Indigenous communities in Alberta and Saskatchewan.