A story of fire and ice: USask research studies how wildfires impact glacier melt

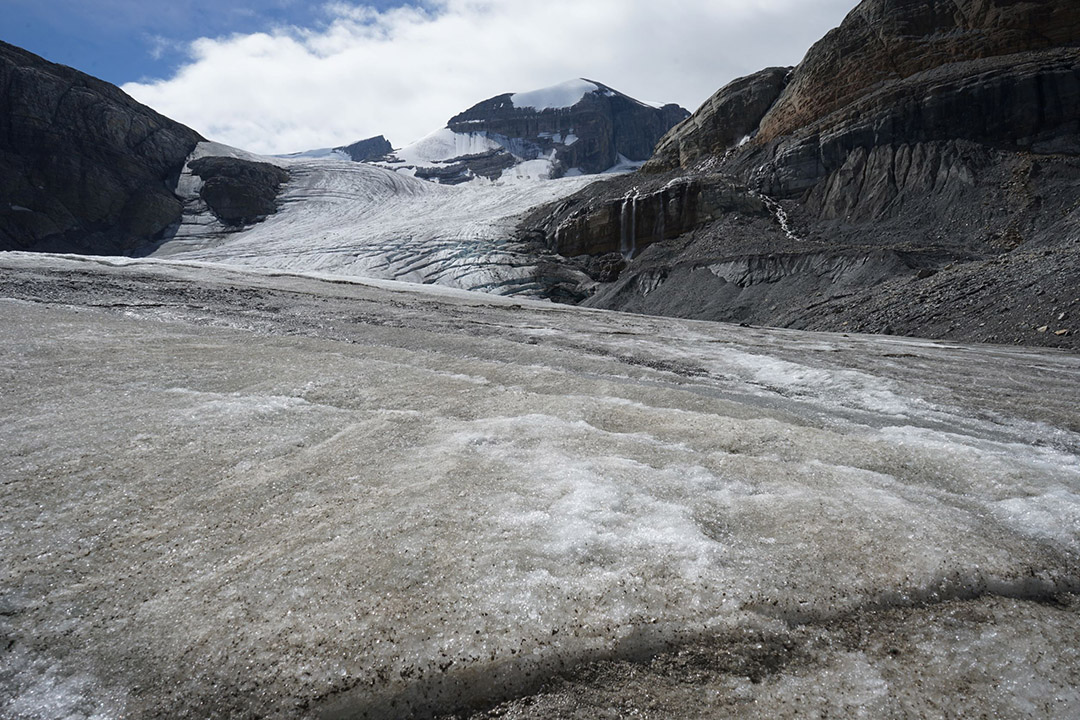

From a distance, the mountain peaks of the Canadian Rockies look like a pristine landscape, untouched by human activity, but Caroline Aubry-Wake experienced firsthand how interconnected our world is while studying the impact of wildfires on the Athabasca Glacier.

By Ashleigh Mattern for GIWS“You wake up in the morning and you go to your computer to work … and you look outside and it’s raining ashes,” said the former Global Institute for Water Security (GIWS) researcher at the University of Saskatchewan (USask).

Aubry-Wake’s research article “Fire and Ice: The Impact of Wildfire-Affected Albedo and Irradiance on Glacier Melt” was published in the American Geophysical Union (AGU) journal Earth’s Future in April 2022.

The research, which was conducted from 2015-2020, found that soot from fires darkened the ice surface and caused ice melt to increase by up to 10 per cent. But in years when there was a lot of smoke in the air, the ice melted less than it would have without the smoke because less solar energy reached the ice surface.

Climate change is not only accelerating glacier melt, but also driving an increase in forest fires, so this work will help deepen researchers’ understanding of the impact climate change has on water resources in mountain regions and across Western Canada.

While there have been other studies about how soot causes an increase in ice melt, Aubry-Wake said how smoke impacts the system hadn’t been discussed much in scientific circles.

“It is a significant advance, just to show that there is a lot going on in the mountains,” she said. “You really have to think about how all these different processes are linked and how they interact together to get the right answer.”

If they had only looked at surface darkening and melt, it would have appeared as though the darkening didn’t have a big effect on the melt. But in fact, the smoke was having a compensatory effect.

In models that simulate glacier melt, it’s sometimes based only on temperature, but Aubry-Wake said that broad approach may lead researchers to miss important details, especially when climate change is causing phenomena and processes that are totally new.

“Trying to understand the granularity … helps us better understand what might change in the future,” she said.

The research was a group endeavour: Aubry-Wake did the fieldwork, co-author and USask PhD candidate André Bertoncini provided applied remote sensing analysis, and the supervisor was John Pomeroy, USask distinguished professor and Canada Research Chair in Water Resources and Climate Change.

Aubry-Wake did the research as a PhD candidate in mountain hydrology with USask, based at the Coldwater Laboratory in Canmore, Alta., but recently started a new step in her science career by taking up a post-doctoral fellowship at Utrecht University in Netherlands after defending her thesis on Oct. 12.

Her PhD research focused on how glacier melt and snowmelt change the mountain landscape and affect hydrology, and her post-doc work will take her studies underground, looking at subsurface hydrology in the Himalayas.

She is excited to be working in a new area of study, but said she will continue to watch how the research develops in the Athabasca Glacier region where she did her PhD work.

“There’s always more science to be done,” she said. “Hopefully, we’ll be able to revisit it in the future and see how it changed.”

Together, we will undertake the research the world needs. We invite you to join by supporting critical research at USask.