USask-led research: Majority of world’s protected ecosystems vulnerable to groundwater degradation

Beneath the surface of the Earth’s protected ecosystems lies a hidden threat—the vast majority of these areas rely on groundwater in danger of being contaminated, drained away, or both.

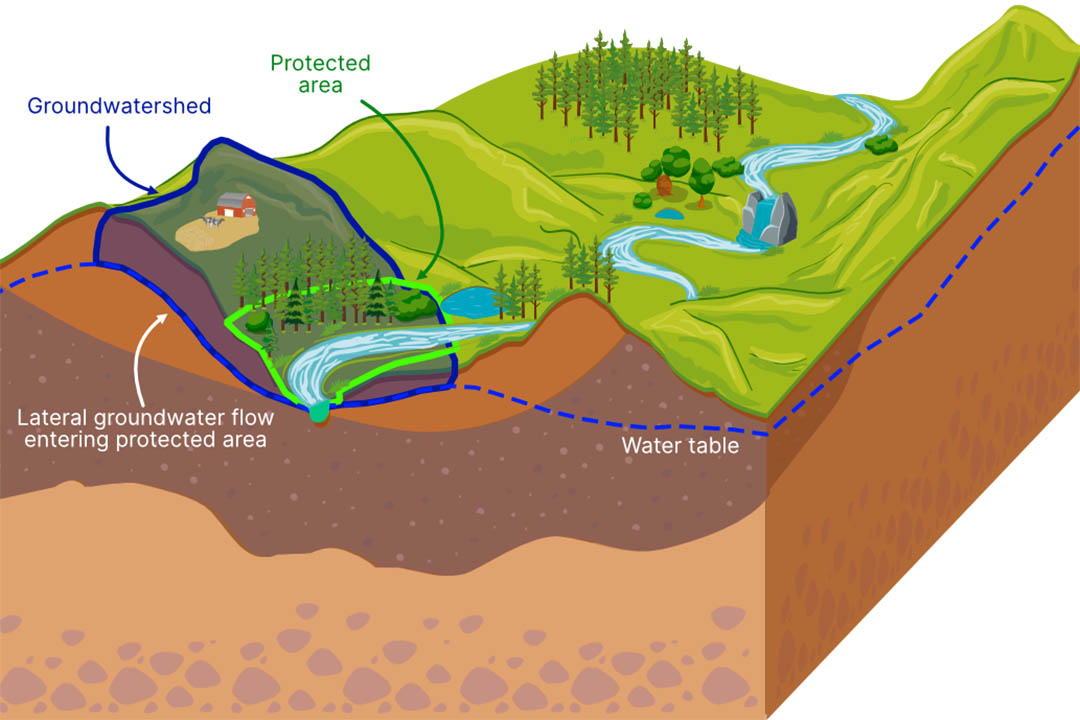

According to analysis published recently in the journal Nature Sustainability and led by the University of Saskatchewan (USask), most of the world’s protected areas—areas like nature preserves and national parks where human activity is restricted—have ecosystems that rely on groundwater. Of these protected areas, 85 per cent depend on groundwater from beyond protection boundaries, leaving ecosystems at risk from exterior contamination and overuse.

“Protected areas can face impacts from activities occurring outside of the protected area, such as agricultural drainage, mining, contamination and groundwater pumping, which can be transmitted to protected areas through groundwater flow,” said Xander Huggins, doctoral student at the USask Global Institute for Water Security and the University of Victoria, and the study’s lead author. “Conservation and management of groundwater-dependent ecosystems stops neither at the protected area boundary nor at the ground surface.”

The researchers gathered and analyzed huge sets of previously published and peer-reviewed data to map the “groundwatersheds”—shallow, local, subsurface water basins where groundwater collects—which feed ecosystems in the world’s protected areas.

The research team mapped these groundwatersheds in approximately one-square-kilometre segments, first determining which direction the groundwater flowed, and then establishing where inadequately protected groundwater feeds into protected areas.

The combined size of the all the groundwatersheds exceeds the total size of the protected areas by nine million square kilometres. Many groundwatersheds span international borders and present political challenges for management.

In December, the United Nations Biodiversity Conference in Montreal concluded with a non-binding agreement of 196 countries, committing to place 30 per cent of the world under protection by 2030 to halt and reverse global biodiversity loss.

“If we want protection and conservation initiatives to be effective, we need to think not just about what's happening on and above the ground, but also the ways that groundwater connects potentially distant areas and activities,” said Huggins.

The next steps for this research involve applying the same approach to specific protected areas, and assessing how quickly and how severely human activities impacting groundwater from outside can impact ecosystems within those protected areas.

Huggins, who is also affiliated with the International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis in Laxenburg, Austria, is supervised by USask professor emeritus Dr. Jay Famiglietti (PhD) and University of Victoria hydrologist Dr. Tom Gleeson (PhD).

The research team also included researchers from University of Kansas, The Nature Conservancy, SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Rohde Environmental Consulting, Conservation International, and from University of Freiburg and Technische Universität Dresden in Germany, and was funded by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Graduate Doctoral program scholarship and by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation).