A farewell to the original USask linear accelerator

Sixty years ago, it transformed the university. Now, it is being replaced.

By Chris PutnamUniversity of Saskatchewan (USask) physicists are remembering the legacy of a foundational piece of research equipment that was retired in 2024.

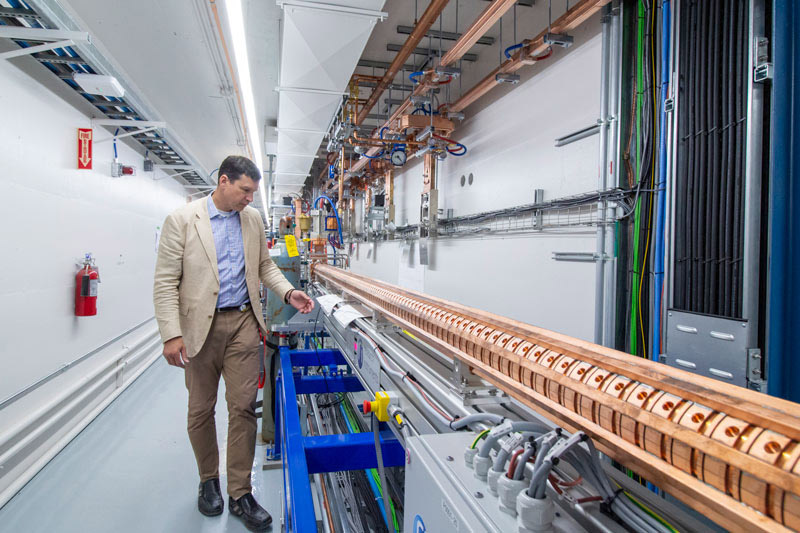

This year was the 60th and final anniversary of the USask linear accelerator, or linac, one of the world’s oldest still-operating machines of its kind. The linac—which drove decades of nuclear physics research and later became a core part of the Canadian Light Source (CLS)—was disassembled this spring and replaced with an updated linac that will be brought online in the coming weeks.

The goal of the upgrade is to ensure the long-term reliability of the machine, which supplies super-fast electrons and ultimately keeps the light on at Canada’s only synchrotron.

“Like your car or your house, as you use it, it wears down. (Parts suppliers) go out of business; new parts get made that are not compatible with old parts. There was nothing intrinsically wrong with the linac, but equipment ages, technology changes, and you need to keep up,” said Dr. Mark Boland (PhD), machine director at the CLS and a professor in the College of Arts and Science’s Department of Physics and Engineering Physics.

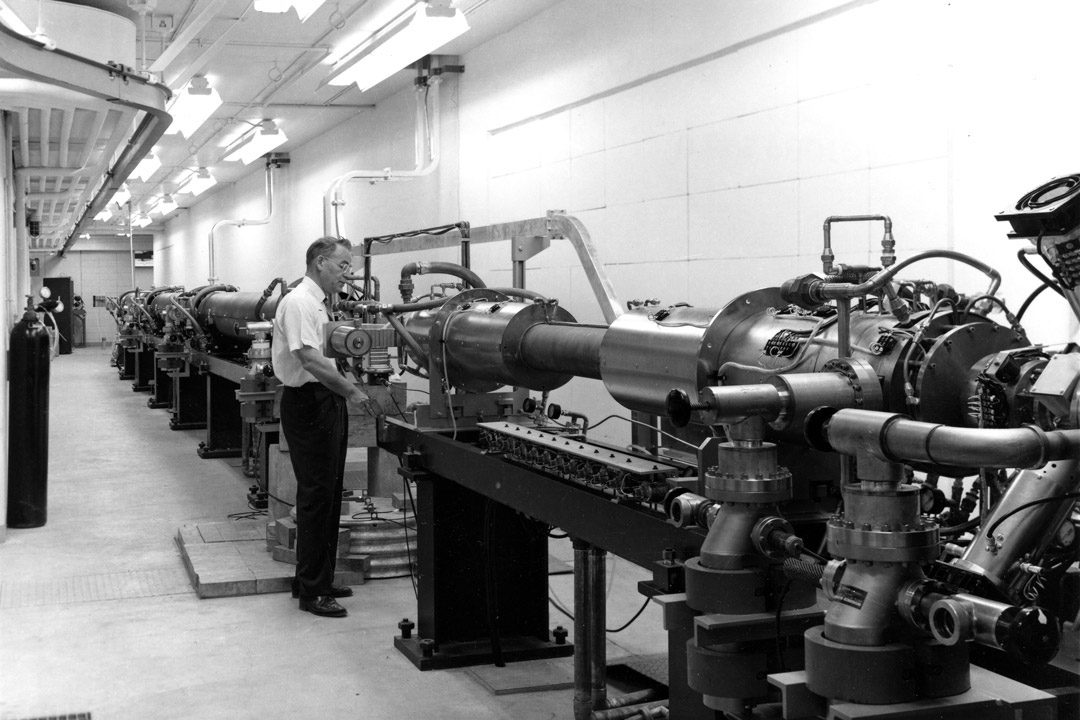

The linac and the Saskatchewan Accelerator Laboratory that housed it were built in 1962 and officially launched in 1964 under the direction of physics professor Dr. Leon Katz (PhD). Jointly funded by USask and the National Research Council, the linac was able to accelerate electrons to an energy several times higher than the betatron previously used for nuclear physics research on campus.

The laboratory helped make USask a major player in nuclear science in the following decades. Researchers from around the world came to Saskatoon to use the linac and USask scientists launched collaborations with many international partners.

For physics professor Dr. Chary Rangacharyulu (PhD), the linac’s place in USask history is inseparable from the work of pioneers like Katz and Dr. Roger Servranckx (PhD). Servranckx, a globally recognized expert on electron ring designs, was recruited by Katz to the mathematics department at USask, where he made major contributions to the linac and eventually to the design of the CLS.

“I tell my colleagues many times, we are very privileged to be on this campus in the Physics Building because of the legacy of these people—the people who were visionaries and made the culture of research on this campus. We are here today because of those people,” said Rangacharyulu.

That’s especially true for Rangacharyulu, who, along with a generation of his physics peers, was drawn to a position at USask because of the linac. When he arrived as a post-doctoral fellow in 1979, there was no other university in Canada with the tools he needed to pursue his work in nuclear science.

“Without this linear accelerator, I would never have thought of coming to Saskatoon,” Rangacharyulu said.

The presence of the linac—and the community of experts that grew around it—was eventually a deciding factor in USask being chosen as the site for the CLS. The CLS was built directly onto the linac and designed to accelerate the linac’s 250 million electronvolt beam up to 2.9 billion electronvolts, where it gives off highly useful synchrotron light.

“You’re basically limited by your imagination what you can do with that light,” said Boland.

The addition of the CLS expanded the linac’s research scope from the nuclei of atoms to matter on a larger scale. Discoveries about everything from battery technology to medicine, dinosaur bones and famous works of art are just a few of the achievements made possible by the CLS since it opened in 2005.

Boland, who came to USask from Australia in 2017 because of the opportunities the CLS offered, notes that much of the research at the synchrotron has a direct lineage to the spectroscopy work of famed former USask physics professor Dr. Gerhard Herzberg (PhD).

“If Herzberg could come and look at the work being done here, he could see his Nobel Prize-winning work being applied here at the Canadian Light Source,” Boland said.

That lineage will continue with the installation of the new linac. As for the original linac, it is not destined for the scrapheap. The CLS is talking to museums and the Department of Physics and Engineering Physics about putting pieces of the old linac on permanent public display. Some parts of the device have also been shipped overseas to be used in the Swiss Free Electron Laser, a linac-based light source in Switzerland.

Boland likes knowing the venerable machine will live on in some way. As someone who worked closely with the old linac for years, he felt something when he watched it be dismantled.

“I'm a sentimentalist at heart, so I did feel that we were losing a bit of something, but we were gaining a lot more,” Boland said.

Rangacharyulu is less romantic.

“Sixty years is a long time for a machine to function…. The linac had a good life, and now we move on. Rest in peace, my linac,” he said with a laugh.

Together, we will undertake the research the world needs. We invite you to join by supporting critical research at USask.